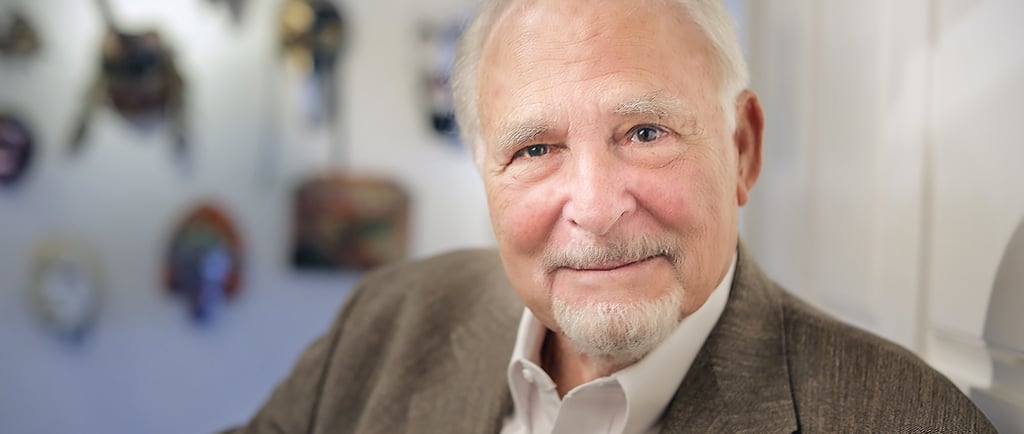

Remembering Paul Ekman: A Pioneer in Emotion Research

Professor Paul Ekman died on November 17, 2025. He was a true pioneer in research on emotion.

AK, Chat-GPT

12/30/20254 min read

Remembering Paul Ekman

In November 2025, the field of affective science lost one of its most unmistakable voices when Paul Ekman died peacefully at his home in San Francisco at the age of 91, surrounded by loved ones. Born on February 15, 1934, Ekman’s journey into the psychology of emotion stretched across more than six decades, touching disciplines as diverse as anthropology, psychiatry, law enforcement, animation, and artificial intelligence. His passing has prompted a wide range of reflections—admiration, personal affection, and also sober consideration of the controversies his work stirred along the way. I had the opportunity to exchange with Paul throughout my career, starting from an internship in 1983, where I was based in Berkeley and visited his laboratory, the famous Human Interaction Laboratory. Springer+1

From his earliest years as a psychologist, Ekman was captivated by a deceptively simple question: What do our faces reveal about what we feel? In the late 1960s and early 1970s, his research took him to remote regions of Papua New Guinea, where he and colleagues studied facial expressions among the Fore people—an isolated community with little exposure to Western media. These studies appeared to be some of the most substantial early evidence that certain expressions of emotion, from joy and anger to sadness and disgust, are recognized across cultures, suggesting an innate, biological basis for at least a core set of emotions. It was work that helped lay the foundation for what we now call affective science. I have read this story many times and remember him delivering a powerful keynote on this at the First International Conference on the Face in 1985 in Cardiff. Paul Ekman Group+1

Much of Ekman’s enduring influence—and his most widely used legacy—was built in collaboration with Wallace “Wally” Friesen, a co-author on the seminal Facial Action Coding System (FACS), first published in 1978. FACS was an ambitious, meticulous effort to describe every anatomically distinct movement of the human face, breaking down expressions into “action units” that could be reliably identified, measured, and compared. This tool quickly became a cornerstone of facial expression research and has been applied not only in psychology but also in animation, human–computer interaction, and affective computing. Friesen’s quiet but substantial role in this work helped shape the standard framework that scientists and practitioners still rely on today. Ekman was also one of the founders of the International Society for Research on Emotions (ISRE), that I had the honor to serve as president from 2013-2018. I remember discussions we had at the meeting in Berkeley, in 2013, where I was elected, where he implored me to work on keeping the society active and relevant in the light of changes in the field. Wikipedia+1

But Ekman’s work was never without debate. His claim that a set of basic emotions and their associated expressions were universal challenged long-standing views that emotions were chiefly shaped by culture and social context. Some critics, such as Jim Russell, argued that the evidence for discrete, universal emotion categories was weaker than Ekman claimed, emphasizing that emotional experiences and expressions vary more continuously and contextually. Alan Fridlund questioned whether facial expressions are primarily social signals rather than direct readouts of internal emotional states. And Lisa Feldman Barrett’s influential theory of constructed emotion contested the idea of fixed biologically hardwired facial patterns, proposing instead that emotions emerge from predictive brain processes shaped by culture and experience. These debates have been vigorous, nuanced, and ongoing, reflecting not so much personal animosity as rooted philosophical and methodological differences about how to understand one of the most complex aspects of human life. (Some of these themes were noted in obituaries and retrospective articles that discussed both Ekman’s impact and the debates his ideas provoked.) Wikipedia

Even within his own field, Ekman’s work was sometimes a matter of debate. For example, while programs such as the Transportation Security Administration’s behavior detection initiatives drew on Ekman’s ideas about microexpressions and deception, later evaluations suggested that untrained observers cannot reliably detect lies visually and that the specific protocols did not perform better than chance. More fundamental methodological critiques pointed out that some of Ekman’s classic studies used selected posed photographs and asked participants to match them with emotion labels—a design that, critics argued, risked circular reasoning rather than testing truly independent recognition. Wikipedia

Yet to focus only on controversy is to miss the scale of Ekman’s contributions. His books—Telling Lies, Emotions Revealed, among others—brought complex scientific ideas into the hands of practitioners and thoughtful readers around the world. His consultancies spanned from helping police and intelligence agencies grapple with deception to advising Pixar on Inside Out, shaping how whole audiences think about the inner world of feeling. And in his later years, inspired by dialogues with figures such as the Dalai Lama, he turned his curiosity toward compassion, meditation, and the role of emotional understanding in reducing suffering—an arc of inquiry that mirrored his own life’s transformations. Parade+1

In the wake of his passing, many colleagues remembered Ekman as a passionate scientist and generous mentor who was unafraid to pose big questions and to follow the evidence where it led. Others have emphasized that the debates his work inspired—about universality versus cultural constructivism, about categorization versus dimensional models of emotion—are among the most fertile in the study of mind and behavior today. Whatever one’s stance in those debates, Ekman’s imprint on how we think about emotion, expression, and human connection endures. He supported me in a couple of critical junctions of my professional career and I am thankful for that.

In honoring Ekman’s legacy, we should also remember the collaborative spirit that made much of his work possible—especially the early and sustained partnership with Wallace Friesen, whose contributions to the development of FACS and empirical studies of expression remain embedded in the fabric of emotion research. Their work together exemplifies how sustained curiosity and meticulous observation can open new ways of seeing something as familiar—and as mysterious—as the human face. research.com

(This text was created with support from Chat-GPT)